Pablo Picasso, a name synonymous with revolutionary art, has often been viewed through the lens of a creator who refashioned the world in his own visage. However, a revelatory exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery challenges this notion, presenting a body of work that delves deeply into the peculiarities of each subject it portrays. This article will explore the surprising truths behind iconic Picasso Portraits.

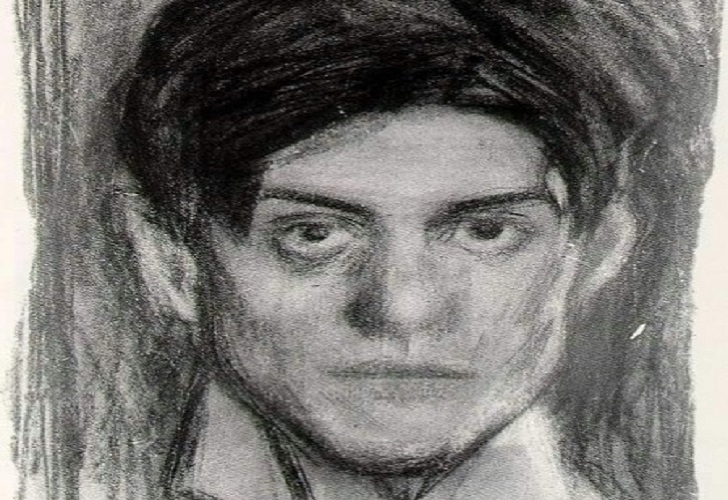

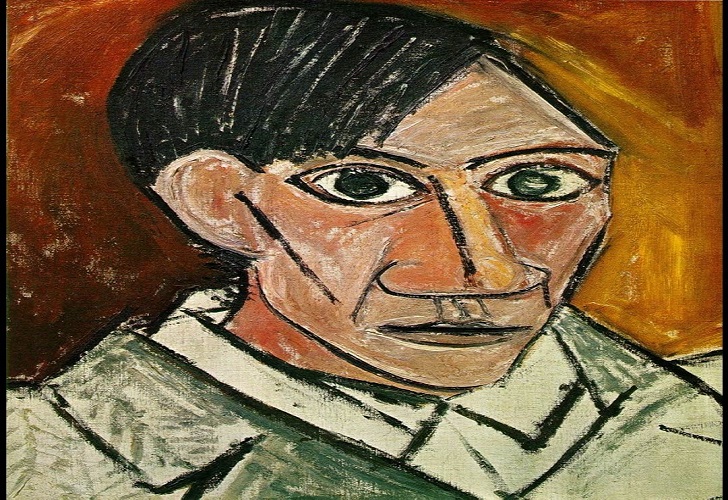

The Self-Portrait that Sets the Stage

As you step into the gallery, the first encounter is with Picasso's Self-portrait with Palette from 1906. This artwork, a blend of pre-cubist and post-blue period styles, presents a young Picasso with a straightforward gaze, yet the portrait does more than meet the eye. It's an ode to the classic art of portraiture, tracing a lineage back to masters like Goya and Velázquez while also nodding to Cézanne's influence and Picasso's own portrait of Gertrude Stein. Here, Picasso is not just an artist but also a continuation of a grand tradition.

@collinpeter925 | Instagram | Picasso Portraits presents a young Picasso with a straightforward gaze.

Exploring Picasso Portraits Beyond the Surface

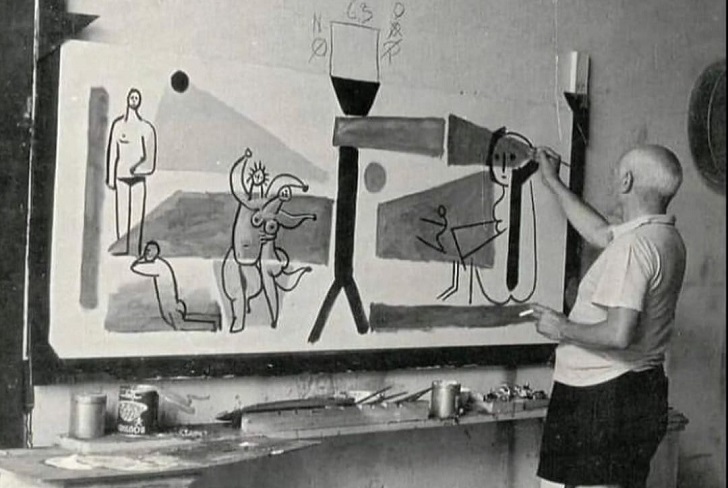

The exhibition titled Picasso Portraits takes us on a journey through the myriad ways Picasso engaged with the human figure. From his blue period’s melancholic tones to the sharp, abstract shapes of cubism, each piece serves as a testament to his relentless experimentation.

Picasso's approach to portraiture was unconventional from the start. Trained traditionally, he was adept at crafting lifelike representations, yet he chose a path less trodden. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Picasso never pursued portrait commissions. Instead, his subjects were often his acquaintances—friends, lovers, and colleagues—each chosen for their intriguing qualities rather than their fame.

Capturing Individuality in Each Stroke

The exhibition's curator, Elizabeth Cowling, emphasizes Picasso's keen ability to capture the essence of his subjects. For instance, in 1938, Picasso painted three different women within a few months. Each portrait, from Woman With Joined Hands showcasing Marie-Thérèse Walter's soft intimacy to the acrobatic tension in the portrayal of Nusch Éluard and the complex depiction of Dora Maar, illustrates a unique facet of their personalities.

These portraits reveal more than just physical appearances; they delve into the personal narratives and emotional landscapes of the subjects. Picasso’s portrayal of Dora Maar, fraught with tension and intricate detailing, encapsulates the tumultuous nature of their relationship, showcasing how his artistic representation was deeply intertwined with personal experience.

The Essence of Caricature in Picasso's Work

The foundation of Picasso's portrait mastery may well lie in his early practice of caricature. These sketches, often created in a humorous, exaggerated style, were not mere side projects but integral to his development as an artist. They allowed Picasso to distil the essence of a person into simple yet profound visual elements. This skill translated into his more formal works, where even the cubist portraits of people like art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler from 1910 carry identifiable traits amidst abstract forms.

Picasso’s portraits are a far cry from mere visual records. They are complex compositions that resonate with the viewer on multiple levels. Whether it’s the expressive agony in Woman in a Hat (Olga) or the cautious tension in Maar's depiction during the Nazi occupation of Paris, Picasso’s works are vibrant narratives compressed into single frames.

The Revolutionary Impact on Portraiture

Picasso's influence on portraiture was transformative. He took a tradition that was predominantly commemorative and propelled it into a realm where it became a dynamic, insightful exploration of human essence and individual identity. Through his portraits, Picasso did not just document; he questioned, challenged, and redefined what it meant to capture someone's likeness.

@pablopicasso_collection | Through Picasso's portraits, Picasso did not just document; he questioned, challenged, and redefined what it meant to capture someone's likeness.

Picasso's portraits are not just about the faces he painted but about the stories they tell and the emotional truths they convey. As this exhibition shows, understanding these works fully requires looking beyond the surface to appreciate the profound depths of Picasso's vision.